Housing Development Under Scrutiny at Special Session

Review shows City lagging on critical affordable housing targets

Review Shows Housing Progress, But What Will Sacramento Say ?

Hermosa Beach's Planning Commission received its first comprehensive status report on Housing Element implementation Tuesday, revealing a city that's checking boxes on process but falling short on the state's core mandate: producing affordable housing.

The two-hour special meeting painted a split-screen picture. Overall housing production is reportedly on track. Administrative reforms are progressing. But after nearly five years into the 2021-2029 housing cycle, the city has produced just two below-moderate-income units—and its efforts to generate affordable housing has yielded zero applications.

By meeting's end, commissioners voted unanimously to recommend gutting one flagship policy—the Land Value Recapture program—acknowledging what critics have said from the start: the fees are acting as a barrier to small-lot development. That’s a problem that flies in the face of Housing Element progress.

What is 'The Housing Element'? (click to see detail)

- The State Mandate: Every California city must update its Housing Element every eight years, demonstrating how it will accommodate its share of regional housing growth. Hermosa Beach's current element covers 2021-2029 and was certified by the state in July 2024.

- The Numbers: Hermosa Beach must plan for 558 new housing units this cycle, broken down by income level: 232 very-low income, 127 low-income, 106 moderate-income, and 93 above-moderate (market rate) units.

- The Strategy: The city rezoned properties through a "Housing Element overlay" that allows residential development on formerly commercial-only sites. The element includes 14 programs addressing everything from ADU development to affordable housing preservation.

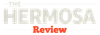

- The Progress: Halfway through the cycle, 384 units are somewhere in the development pipeline—from applications to completed construction. The city claims that it is on track to exceed its market-rate housing target.

- The Problem: All 384 units in the pipeline are market-rate housing. Zero affordable units have been proposed or built, meaning the city is falling behind on its affordable housing obligations across all income categories—a failure that could trigger state penalties and "builder's remedy" provisions that override local zoning controls.

- The Regional Context: Neighboring Redondo Beach's Housing Element is currently being challenged in court, illustrating the legal risks cities face when their housing plans don't satisfy state requirements. A failed Housing Element can result in loss of local control over development decisions, and there are strong similarities between our plan and the Redondo plan.

The Report Card

Community Development Director Alison Becker, seven months into the job, gave the city an "A minus, B plus" on implementing 13 housing programs spanning five policy areas: conserving existing housing, supporting new production, providing adequate sites, removing governmental constraints, and promoting equal housing opportunity.

The numbers look respectable at first glance. The city's Regional Housing Needs Allocation requires 558 units by 2029. At mid-cycle, Hermosa has 184 units in the pipeline with 116 completed—right on pace for the total.

"From a total production perspective, we're right on target," Becker said.

But the state doesn't just count total units. It allocates them by income category: very low, low, moderate, and above-moderate. And that's where Hermosa's numbers reveal a problem.

"The challenge is that we're underperforming in the very low, low and moderate income categories," Becker said, understating what the numbers show: of those 184 units in progress, essentially all are market-rate.

Commissioner Pete Hoffman put it more bluntly: "We've done all the drills. We're making progress. But we're outscored 370 to two in the low-income housing game."

What's Behind Schedule

Three areas drew particular concern:

City-owned sites for affordable housing. The Housing Element committed to identifying a site, issuing an RFP, and beginning a project by 2025. With departmental turnover, "this initiative hasn't yet been started," Becker said. "We can definitely pick that up in the coming year."

Mixed-use zone expansion. Originally scheduled for 2025, now pushed to 2026.

Local Coastal land use Plan Committed for 2024, delayed due to department transitions. "We're in the process of resuscitating that effort," Becker said.

The delays matter because the state Housing and Community Development Department emphasized in its certification letter that it expects "timely and effective implementation of all programs."

The Redondo Beach Problem

The meeting occurred in the shadow of October's New Commune v. Redondo Beach appellate decision, which decertified Redondo's housing element. The court found that overlay zones permitting—but not requiring—residential development failed to meet state density requirements.

Assistant City Attorney Sarah Locklin walked commissioners through the implications. The key finding: sites with base zoning that allows 100% non-residential use don't satisfy the state's 20-units-per-acre residential density requirement, even with a residential overlay.

"This is the part of the case that is really new to us," Laughlin said. Many jurisdictions relied on HCD guidance when creating these overlays. Now a court has said that's not enough.

Hermosa's housing element remains certified—for now. But staff is reviewing the overlay program to determine if sites need rezoning to mandate residential components.

"We are taking a look at our current site inventory list to determine if we need to make any improvements," Laughlin said, noting Redondo Beach plans to appeal and HCD hasn't issued guidance yet.

Resident Anthony Higgins raised another concern: St. Cross Episcopal Church, which the city allocated 46 low and very-low-income RHNA units despite knowing the church planned to keep operating its school and sanctuary.

"We all know it was a scam," Higgins said. "Does that put us at risk of decertification? And where exactly are those extra units we're going to need going to come from?"

The ADU Opportunity—And Accounting Problem

One bright spot: accessory dwelling units. Hermosa has embraced ADUs, and they're producing actual housing.

But there's a catch. The city hasn't been accounting for them properly. Southern California's regional methodology allows jurisdictions to allocate ADU production across the affordability spectrum—very low, low, moderate, and above-moderate income—based on statistical analysis.

"We haven't yet done that sort of distribution for our housing units," Becker said. The department is building new data systems to track ADUs properly and retroactively allocate completed units across income categories.

That accounting change could significantly improve Hermosa's numbers in the lower-income categories. How much? Becker wouldn't estimate. "I'm hopeful that at our next annual progress report... we'll have a better sense."

Jon David, a commercial property owner, urged accuracy: "I was really surprised at the last APR before Alison came. We had seven ADUs and none were allocated. They were all market rate."

The Failed Program

Which brings us to Program Six: Land Value Recapture (LVR).

What is 'Land Value Recapture' ? (click to see detail)

- The Basic Concept: When a city rezones property to allow more valuable uses (like adding residential development rights to commercial-only land), the property value increases. Land Value Recapture policies require property owners to share a portion of that windfall with the public.

- How It Works in Hermosa Beach: Properties that gained residential development rights through the Housing Element overlay can either include affordable housing units on-site OR pay a per-square-foot fee when they develop.

- The Fee Structure: Smaller properties (4 or fewer units) pay $76 per square foot; larger properties (5+ units) pay $104 per square foot. These fees go into funds for affordable housing development elsewhere in the city.

- The Exemption: Developers can avoid the fee entirely by making 15% of their units affordable to very-low or low-income residents, or 25% affordable to moderate-income residents.

- The Goal: Generate funding for affordable housing or incentivize developers to build affordable units directly—ideally making the fee high enough that developers choose to build affordable housing rather than pay.

- The Reality: Since taking effect in August 2024, not a single development application has been submitted on affected properties—no projects with affordable units, no projects paying the fee. The policy designed to create affordable housing may instead be preventing any housing from being built at all.

Approved by City Council in January 2024 and effective since August when the Housing Element was certified, LVR charges developers $76 per square foot for small projects (four or fewer units) or $104 per square foot for larger ones—unless they include affordable housing on site.

The policy applies only to properties rezoned from commercial to mixed-use through the housing element overlay. The theory: if the city creates value by allowing residential development, it should capture some of that value for public benefit—specifically, affordable housing.

After 15 months: zero applications. Zero revenue. Zero affordable units incentivized.

Small lots—those accommodating just one to four units—represent 137 of the city's 558-unit RHNA allocation. That's 25% of the obligation, sitting idle.

Becker noted that no applications have been submitted on overlay sites that would either include affordable units or require LVR fee payment. "This could be market conditions. It could be feasibility. It could be timing."

Jon David warned that the program makes four false assumptions: high demand from commercial owners, windfall profits that can be captured, public entitlement to rezoning benefits, and workability as a paper exercise.

"The LVR program collapsed" demand that existed in 2022-2023, David said. "You cannot ignore the economic reality, especially in the postage stamp size lots, in the coastal zones with existing uses.

"You cannot overcome the lack of demand or inertia unless you give people a reason to do it," David said. "You need carrots, not sticks."

Recommended Changes

After an hour of debate, commissioners crafted a unanimous recommendation combining three of staff's five options:

Option B: Completely exempt properties that can build only one or two units from any LVR fee.

Option D: Direct staff to explore zoning regulations that could actually encourage residential development on small lots—perhaps forming a working group with property owners, architects, and city officials.

Option E (modified): Temporarily reduce fees to $40 per square foot for 24 months on three- and four-unit properties.

The recommendation leaves unchanged the fees for larger developments (five-plus units).

Vice Chair Izant argued against full exemption: "The overlay has created an economic benefit... I cannot support just giving away 100 percent." But he supported significantly lower fees for small lots combined with exploring what actually prevents development.

Commissioner Hoffman framed the LVR program more harshly:

"This program failed. This is program seven in our programs to accomplish the RHNA numbers. Let's get rid of that, at least for the small lot properties."

Chair Hirsh noted the market timing problem: "Property values have actually gone down for most of us in Hermosa Beach. The cost of construction has gone way up. Interest rates for loans have gone up."

Commissioner McNally, who joined the commission after the LVR program was approved, said: "As a homeowner and someone who has owned businesses... I just can't even fathom another hurdle, restriction, cost to come my way."

What Happens Next

Both items now move to City Council.

The Housing Element progress report will likely return annually, ideally coupled with the April submission to the state. Becker said she'd welcome suggestions on review frequency.

The LVR recommendation faces a more uncertain path. Our current council looks different to the one that implemented this much-criticized initiative. It seems likely that they will walk it back, perhaps even more forcefully than the Planning Commission recommendation.

The state requires biennial review of the LVR program. That review just came early, prompted by Council's March request and a year of zero results.

Becker emphasized that Hermosa's Housing Element remains certified and the city is implementing programs effectively. But she acknowledged the reality: "The RHNA numbers are targets, and our obligation is to plan."

Commissioner Hoffman opined that low-income housing will likely get built through density bonuses, tax incentives, and government partnerships on large sites—not through land value recapture on 3,000-square-foot lots in the coastal zone.